By Dudley Brown

The challenges and achievements Chaplain William Andrew White Jr. experienced offer valuable lessons for modern 21st-century Chaplains.

Despite the differences in eras, the enduring parallels in religious, cultural, and sociopolitical climate prompt reflection on how his life and values can inform and strengthen chaplaincy today.

Early life

Born in 1874 in Virginia, just after Civil War, Rev. White’s theological formation was nurtured during the periods of Reconstruction and Redemption, then succoured by his Pastor, Rev. Beverley Sparks, a learned former slave who promoted education as a means of Black self-improvement, and the Rev. Dr. Harvey Johnston of Baltimore’s Union Baptist Church, a civil rights pioneering of the late 19th-century.

White went on to be educated at Wayland Seminary, an institution whose legacy of service to the Black community included Booker T. Washington and Adam Clayton Powell as alumni.

White’s exposure to social justice initiatives, overt altruism, and social protest supported the burgeoning leadership qualities of a young and impressionable man of God.

Encouraged to attend Acadia University in Canada, White could not engage in the social and cultural aspects of university life due to discriminatory practices. White met these daily indignities with a gentlemanly bearing, genuine humility, humour, and a kindly nature. Upon graduation, he became a missionary in Nova Scotia, founded New Glasgow Baptist Church, entered the pastorship of Zion Baptist in Truro, before becoming Chaplain of the No. 2 Construction Battalion during The Great War.

The life arc of Rev. William Andrew White Jr. laid the groundwork for the Canadian Civil Rights Movement by attacking discrimination wherever he saw it in the same manner as Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. (i.e., with the love of God and the goal toward a brotherhood of humanity). And, like MLK, he became a devout advocate for the Black community and the emissary to the White power structure.

For White, these attributes were forged in the crucible of War.

Pre-War

Black leaders believed gentility, industry, and education would lead the White power structure to grant the Black community full citizenship (an ideology called the Politics of Respectability); thus, serving in war and showing Black patriotism was seen as a vehicle to acquire socio-political acceptance and citizenship.

However, Blacks were rebuffed at the admissions office. White responded by petitioning the government to allow Blacks to sign up to fight; in acquiescence, the Canadian government agreed to a segregated division, the No. 2 Battalion.

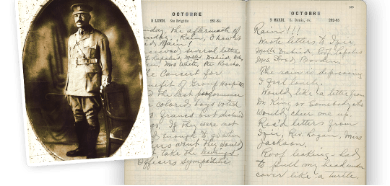

Originally a combat unit, racist stereotypes saw Captain White and the No. 2 relegated to a construction battalion, an eventuality they did not learn about until they were training in France. As Chaplain, White’s leadership acumen assuaged the men’s disappointment and anger over the situation; he shared time with his men, offered them his services in financial matters, comforted them in the hospital during convalescence, took pride in their talents as musicians and athletes, and charted their baseball games and musical concerts. He advocated for fair treatment of his men and encouraged them to hold their heads high in the face of daily discrimination. He kept a diary in which he wrote to his wife and of his men; he also wrote to the Black communities of Ontario and Nova Scotia via the newspaper.

Initially the Chaplain for all soldiers, White later found that the White soldiers did not want a Black Chaplain.

Demobilization

Wanting to return home, the troops became angry at the bureaucratic bungling of the flawed demobilization process. An incident between a White regiment and The No. 2, now showing their repressed frustrations, saw the situation devolve into what would have been a race riot. In an act of courage and moral authority, Chaplain White placed himself between the two angry groups, thereby pacifying the situation.

War’s End

It was believed that service in the war would give equality to Blacks, but it did not; being forced to confront the limitations of Blackness in Canada, White used this revelation to revise his theology and praxis for Black uplift and full citizenship.

When White left the Chaplaincy, he began to lay the groundwork for the Canadian Civil Rights Movement: he became the pastor of Cornwallis St. Baptist Church, a leader in Black uplift and advocacy; he became the first Black preacher to broadcast his sermons across the Maritimes and the northern-eastern United States, regularly reinforcing his praxis for Black attainment of full citizenship and calling for racial unity and understanding; and he was the first Black to speak before the Nova Scotia Baptist Convention on race relations in Canada, where he showed how he was harmless as a dove and wise as a serpent. White’s speech not only fit neatly into today’s socio-political and cultural milieu, but this stance and theology continued his building of one of the foundational elements of his praxis for full citizenship, race consciousness.

Chaplain White met each hurdle with grace, love, and an intellect that shaped a calm, measured response that promoted the Kingdom. Although White died before Viola Desmond’s stand against discrimination prompted the start of the Canadian Civil Rights Movement, those who championed the cause used the foundation he had built.

* * *

Dudley Brown, PhD, is an independent scholar of Church History and Assistant Editor of Post-Christendom Studies.

**The views of this Blog represent those of the author, and not necessarily the CBHS.**